- The war in Syria has almost completely destroyed the country while destabilising its neighbouring countries, a situation that has spurred the governments in the region to ignore things like the cultivation of cannabis, previously strictly watched for and punished. Very close by, the continuing conflict between Israel and Palestine maintains the blockade and the closing of borders, forcing Israelis to grow their own marijuana, which previously came in over the Egyptian border.

Four years have passed since in May of 2011 Syrians initiated a peaceful revolution against the government of Bashar Al Assad. That revolution led to a civil war that has left many dead, in addition to producing forced migrations and refugees, and completely destroying cities. This is a war that has caused governments in the region to dedicate all their efforts to contain the terrorist groups that could spill over Syria's borders, leading them to forget about (fortunately for growers) other issues, like the cultivation of cannabis, formerly on the authorities’ agenda.

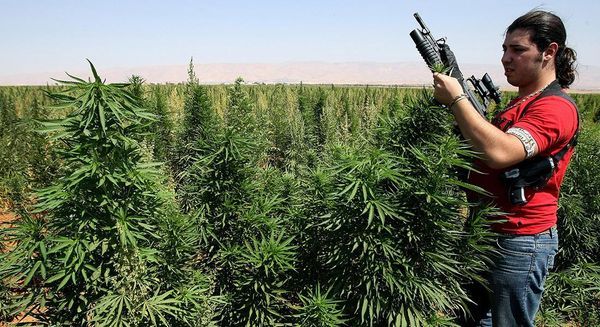

Marijuana plants in the region freely flourish, and are harvested and prepared to be sold directly on European streets. In countries like Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, Jordan and Egypt they cover fields formerly used to grow beets. The Middle East has become the centre of a multimillion-dollar business, with growers belonging to armed groups in each country that, in a way, also help to keep the area under control while they do their jobs, surrounded by AK47s, machine guns and rocket-propelled grenades.

Lebanon, the vortex of production

To understand the situation in Lebanon, there is nothing like analysing Ali Nasri Shamas as a figure, one of the men behind cannabis cultivation in the country of cedars, and considered by all a kingpin of the business. With his own marijuana producers on his payroll, he also buys product from smaller farmers, creating an empire, now with hundreds of people working for him. He reports that the harvest was good this year, and that his main producers will make at least a half million dollars each. Thus, he is willing to do anything to keep the government from getting near his plantations: “We are selling hashish, and if anybody from the government gets close, we'll kill them.”

He even defines himself as a Robin Hood figure that fights against local corruption and wants to distribute wealth in the region. However, areas flooded with marijuana have caused prices to plummet, due to the excessive supply; two years ago growers could sell a kilo of hashish for about €1,200. Now the price is just one fourth of that. Nevertheless, cannabis continues to be the most lucrative business around.

For years Ali Nasri Shamas and other Lebanese growers saw their illegal crops burned by the government. But since the army has focused on stopping military groups trained in Syria, which were becoming more powerful in the country, his plants have bloomed untouched. Now the farmers here, especially in the area of the Bekaa Valley, say they feel more protected, and that they do not worry about the raids which the police and other armed groups used to carry out against their crops. The farmers' families no longer go hungry, and they have money to pay for heating and their children's education, which is why Shamas is determined to keep the landscape green, at least until the situation improves in other aspects.

His workers explain that their crops are nothing new, although now they have increased, and state that the land that they work belongs to the people, such that the government has no right to tell them what to do with it. There are many who, reacting to the country's indifference and the lack of protection it provides them, prefer to join the groups controlling the plantations, in order to enjoy some kind of protection in an area that is not at all safe, and a job that allows them to live amidst so much misery.

Hezbollah, between two lands

The crops, however, are also protected by Hezbollah, a Lebanese, Shiite paramilitary organisation that stokes the war, supporting the Syrian government. In this case, a part of the cannabis that they grow is earmarked for the combatants, so that they are better able to fight, and can forget everything they have been through. But most is exported by sea from Lebanese ports, or passes through Syria on land, a country where Hezbollah is fighting on the side of President Bashar Al Assad.

As a result, the Lebanese marijuana and hashish produced by Hezbollah today is able to easily reach the markets of Dubai, Jordan and Iraq. And, most importantly, it also satisfies the increasing direct demand from Syrian consumers.

But, in what is a strange contradiction, Shiite growers also sell their grass to the Syrian regime's fierce enemies: the Sunni militants of the Islamic State (ISIS), by extension their sworn enemies, but good friends with which to do business with cannabis, to whom they sell tonnes, even within Lebanese borders.

Just last year a video came out of ISIS combatants burning a cannabis field in Syria, with jihadists denouncing the evils of drug consumption. But it seems that Islamic law is not really dedicated to keeping all radicals far from the “bad grass.” The fact is that Sunnis, Shiites and Christians often live next to each other in this Lebanese valley, already considered a key source of cannabis for the international market, to the point that religious motives are not enough to defy the laws of supply and demand.

Those most harmed by this business, however, are Syria's refugees, who cross the border fleeing the war, and who are supposedly being used to process the hashish as cheap manual labour, while officials in the Christian army are those who channel the large-scale smuggling to towards the Mediterranean.

In the end the Syrian conflict has had a direct impact on this country, where tourism has collapsed, as has the real estate market, and food exports have significantly dropped too. With the Lebanese economy in a general freefall, cannabis production has become the only reliable source of income in a country surrounded by hot spots.

Turkey grapples with the PKK

On Syria's northern border the cannabis situation is also dicey. Turkey has done much to promote the financing link between the hashish trade and the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK), a separatist guerrilla movement that for more than a generation has been waging an insurgent war in the east of the country. Of the 150 tonnes of hashish that were seized in 2013 in Turkey, almost 89 came from the southeast of the province of Diyarbakir, a fertile mountainous area in the heart of Kurdish territory, some 200 kilometres from the Syrian border and where it is estimated that more than 60 towns depend upon the cultivation of vast fields of cannabis running between the crags there. In comparison, in 2012 only 13 tonnes of hashish were confiscated in the same area.

In March of 2013 the jailed leader of the PKK, Abdullah Ocalan, declared a historic cease-fire after months of negotiations with the Turkish government, which Turkish security forces took advantage of to initiate operations against marijuana fields in the areas which they previously could not access due to the threat of terrorism. The marijuana crops in the mountainous areas were detected mainly thanks to satellite photographs and joint police/military operations were carried out with the support of helicopters, and hundreds involved in the raids. It is estimated that some 56 million plants were destroyed during the months when these operations took place, until the PKK announced that it was suspending the truce, accusing the Turkish government of not delivering on the reforms it had promised.

Since that time, the marijuana fields in southern Turkey have been protected by anti-tank mines, with snipers occupying high positions to protect them from intruders. In addition to these arms, there also exist great legal impediments to the prosecution of growers. The growing of marijuana is only punishable by prison sentences of less than one year. Moreover, the Turkish Penal Code lacks dispositions allowing public prosecutors to investigate the assets of those suspected of having acquired their wealth through drug trafficking. And, as the fields are not registered in anybody's name, nobody is liable for the illegal use of the land.

In this way the PKK continues to evade effective monitoring by the police, while it establishes command posts to control production, and even builds wells and pools to meet fields' irrigation needs. In this way this paramilitary group has taken complete control of the marijuana trade in the region, without the Turkish government being able to do anything to stop it.

Israel, self-sufficiency as a necessity

On the opposite end, Lebanon's main enemy in the area, Israel, faces a very different reality. The continuous conflict between Israel and Palestine has led to constant border blockades, impeding access to some products, like certain foods and marijuana. When the border between Gaza and Egypt was open cannabis was cheap and easy to obtain, but now it is up to five times more expensive, as the border with Egypt remains closed most of the year, and the border fence, supposedly established to control terrorism, means that Israelis do not know whether they will be able to smoke marijuana from one day to the next.

In fact, until the closing of the borders, close to ten tonnes of hashish, 70% of the cannabis consumed in Israel, entered every year from Egypt. It was in 2010 when things changed, especially due to the construction of a barbed wire fence on its border with the Arab country. Now small amounts of marijuana continue to enter through Jordan, or over the Red Sea, but most merchants inside Israel have lost their regular suppliers and do not have practically anything to sell their former customers. This, according to some users, means that there is a certain danger of buying unhealthy marijuana, as the safety of the substances has been affected by the shortage, and desperation to find something to smoke.

Israelis have no choice but to grow their own crops. “People even grow in their own houses, and I myself buy from those who are producing,” explains Oren Lebovich, an activist who supports the legalisation of the cannabis there. They are many (estimates cite some 60,000 people) who have decided to use their own growing equipment and to produce, making good amounts of money and turning their activity into one more way to make a living, especially in Tel Aviv.

All this is happening in spite of the legal consequences that their growing could entail, as the use and distribution of marijuana are officially illegal in Israel, except for medical use. In fact, police raids on growing areas are common, and every year dozens of growers are arrested, along with workers from Thailand suspected of cultivating cannabis in greenhouses. These are immigrants who find it difficult to live off the sale of peppers and tomatoes, and who see their future in the green plant and the closing of the borders. Arrests related to cannabis and other substances, altogether, come to 20,000 every year.

The settlers living in the West Bank are also increasingly involved in the world of marijuana, with taking on a role as distributors of cannabis and other substances, especially due to the scant police control in these territories. This situation draws Israelis towards these places, where they tend to spend several days on each trip.

The activist, Levobich, explains that in spite of the marijuana shortage affecting his consumers, this situation has managed to encourage home growing and crops that are much safer, at the same time allowing Israelis to cease from financing their main enemies, like Hamas in Gaza, which regularly benefitted from the cannabis trade.

In the Middle East the growing and consumption of cannabis casts shadows, but also light. For some the war has provided a perfect opportunity to grow, harvest, enjoy protection and not go hungry. The conflict has spurred others to grow for themselves, without depending on external farmers, which increases the quality of the marijuana that they produce. The only certain thing is until the hostilities cease in the maelstrom of Syria, this situation promises to continue.

-----------

Photos: imlebanon.org and Ruth Sherlock

Comments from our readers

There are no comments yet. Would you like to be the first?

Leave a comment!Did you like this post?

Your opinion about our seeds is very important to us and can help other users a lot (your email address won't be made public).