- Certain social developments seem unavoidable, even in a country that attaches so much importance to its history and so much value to its secular traditions. As unavoidable as it may be, the debate about the legalisation of cannabis is still enchained by mental images and clichés that have been inherited from a long history.

France is known in Europe and throughout the World as one of the countries that is most radically opposed to cannabis. Even medical usage at the moment is limited to a single medication, SATIVEX. Mere usage constitutes a criminal offence, and the perpetrator may face up to a year in prison, in a country where there are 550,000 daily smokers and 3,000,000 occasional users. Without going as far as saying that the latter are subject to systematic persecution by public authorities, it is nevertheless reasonable to think that the repression they are subject to is excessive in proportion to the threat that they represent to public order.

This demonization of cannabis has its roots in France’s hidden colonial past. In the 17th century, hemp was already a strategically important fibre, grown under strict state surveillance. Its resistance made it the material of choice for manufacturing the sails of ships that allowed Louis XIV to engage the country in the long-term adventure of colonial expansion. During that period, colonialism was primarily about the exploitation of slaves: there was a large estate type economy, based on the exploitation of forced labour that produced sugar cane and alcohol, which was already very valued in France. Following that period, cannabis was perceived in France as a product linked to indigenous people from southern countries: Africa, the West Indies, and the Indian Ocean; it was the medication of slaves, and usage was tolerated and even encouraged on plantations during the colonial period. This conflict between alcohol and cannabis was to be long lasting and still influences the perception of the problem today.

Four centuries later, according to a report by the OECD published in May 2015, France is still well ahead in terms of being the world’s leading alcohol consumer per habitant. An average of 11.8 litres of pure alcohol is consumed each year per citizen, as opposed to 9.1 litres in the other 34 countries studied. The consumption of alcohol is socially encouraged there in many ways, from family conviviality to consumption at the counter in cafés and bars. The French wine making culture is revered throughout the entire world, and we should not forget to mention the export revenue generated by actors such as the producers of cognac, champagne, or the big Burgundy and Bordeaux dealers. It is therefore logical that cannabis is so demonised there and that alcohol is so valued. From a strictly medical point of view, the two products can both lead to serious addiction however society is unable to see that and even less to treat them on equal terms.

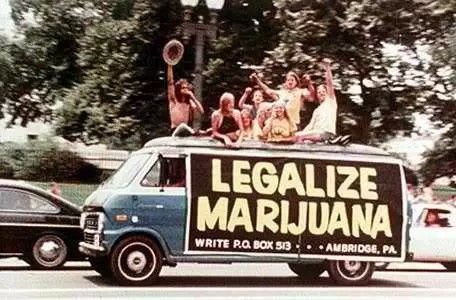

It is necessary to go back to May 1968 in order to get a better understanding of the symbolic scope of cannabis in society and the taboo that decriminalisation represents in political discourse from both left-wing and right-wing politicians. The American army’s stalemate in Vietnam made that war the last of its kind. This final decolonisation conflict led to a wave of pacifism and libertarianism, first in America and then worldwide, and this manifested itself in the hippy movement. France at that time still lived under the iron grip of De Gaulle, in a society comprised of institutions that were certainly democratic, however often authoritarian, coercive and brutal out on the job; there was police violence, torture and summary executions, even mass killing in Algeria, brutality within teaching, legal conservatism, and State racketeering. In May 1968, students took to the street with a radical response to the type of society them found themselves in which citizens seemingly only knew how to function when being kicked around. The decriminalisation of cannabis was part of their program of “revolutionary” transition towards a “more intelligent” society, in which it would be “prohibited to prohibit”.

Following that era, the image of the cannabis leaf was to be closely linked to the subversive events that had marked the decade. After 1968, the right returned to power with Georges Pompidou, and it quickly had to provide some signs of being reactionary and security obsessed to the well-off electorate and the lobbies of the military-industrial complex, that were paralysed by the episode of the barricades and general strike. It was cannabis that would immediately take the blame and be turned into the standard against which state firmness and the restauration of authority could be measured. Cannabis was a scapegoat that was regularly sacrificed on the altar of conservatism during the electoral period.

It was indeed in this context that the law of 31 December 1970 with its famous article L-627, was voted in, and all current regulations are still based on this. It marked a certain return to “normality” for the Republic’s moral order by making every user a criminal, or in the best of cases, someone that was mentally ill, according to the judge’s reasoning. The penal transaction that was recently decided and voted on, should not get peoples’ hopes up. It is only an additional weapon of repression within a well-stocked arsenal. Since 1970, numerous societal reforms have accompanied France’s modernisation; the law of 1973, with Simone Weill legalising abortion, the abolition of the death penalty in 1981, and more recently, the law passed allowing marriage for everyone. In terms of cannabis, legislation seems to have remained the same as if it had been issued from the hand of God on to sacred marble tablets.

The outright hostility of the right to any advance is also quasi-ideological and has never ceased during the course of the last four decades. The right has proclaimed itself champion of the security cause, and following the 1970s, cannabis has readily been found to be the symbol of permissiveness. In turn, the left-wing has always been cautious so as not to be labelled naive or permissive by those on the right. Certain socialist ministers (Bernard Kouchner, Daniel Vaillant and, more recently, Vincent Peillon), have sometimes gone as far as to make a modest declaration on the absurdity of current legislation and shown interest in “shaking the dust off” regulations. They have all been sharply called to order by the Prime Minister or the President, worried of appearing to the public to be lagging behind in the discourse about firmness. This is a more sure-fire means of seducing the electorate. Only the Greens and certain parties on the extreme left are in favour however they still only have marginal electoral power.

It is therefore necessary to state that the cannabis matter has only been tackled in terms relating solely to security as if it constituted a threat to public order. Cannabis is imprisoned by a libertarian and transgressive image that has been inherited from the distant past. The prevailing view associates it unconsciously with the “chienlit” (De Gaulle’s pun meaning “shit-in-bed” i.e. chaos)as well as subversion and insecurity. This happens as naturally as wine is associated with conviviality, the art of living “the French way” and the development of wine growing areas. These ideas imbue the collective unconscious and only evolve very slowly. The 63% of people surveyed in 2013 that were opposed to any progress towards liberalisation is reduced by one or two percent every year and this decrease is a prevailing trend. However, until this number is significantly below 50%, it will be difficult to imagine a significant legislative advance. Optimists will therefore say that it is simply a matter of time and that perhaps political courage will play a role in speeding up this matter.

Comments from our readers

There are no comments yet. Would you like to be the first?

Leave a comment!Did you like this post?

Your opinion about our seeds is very important to us and can help other users a lot (your email address won't be made public).